She designs the clothes women actually want to wear

Just when fashion needed new direction, Phoebe Philo has returned from self-imposed exile to present a vision of how to dress today. After a single season as the creative director of Céline, Phoebe has cut through fashion’s tired fantasy, turning the dust-gathering Parisian house into a platform for sharp reality and hyper-luxurious clothing. In person, Phoebe is an intriguing mix of British reserve and disarming frankness; she has long been an inspiration to the legions of women, young and old, who want to be just like her. Phoebe is always her own best model, designing clothes that suit wherever she happens to be in life.

Having learnt the lessons from her past position at Chloé, she is now ensuring that the Céline design studio is based in her hometown of London rather than at the company’s headquarters in Paris. That means Phoebe can live a full life with her two children and husband, Max – a contemporary family setup that greatly informs her work.

One might wonder at the thoughts crossing LVMH CEO Bernard Arnault’s mind as he sat on a bench in a disused office space last October, clutching an anthology of grainy images that had more in common with a copy of Penthouse from the 1970s than a glossy brochure for Céline – the last bastion of the bourgeois French fashion plate. With not a press statement in sight, the stylish picture book was a gift for everyone there to witness Phoebe Philo’s long-awaited debut runway show for Céline, the venerable house that for seven decades has dressed Parisian matriarchs who couldn’t quite stretch to Chanel but still had a penchant for bouclé tweed and a gilt button. In what was almost a memorial service to the legacy of BCBG, both book and collection demonstrated that the brand’s future would be replete with beautiful, powerful and, above all, ultra-modern women.

“I surround myself with images for their emotional qualities,” says Phoebe when I meet her at the recently restored Georgian townhouse in Cavendish Square that Céline has made its London headquarters. “I get an energy from their tenderness, strength and glamour that I’m very responsive to.” It is the Friday before a big collection deadline so members of Phoebe’s team are adding finishing touches to fabric research in the studios downstairs. The contemporary artwork decorating the oval staircase up to Phoebe’s office certainly hints at this emotional sensibility. While a vast seascape by the French photographer Marine Hugonnier brings meditative calm to the busy lobby, Brit artists Tim Noble and Sue Webster’s Forever light piece sparkles romantically in the austere hallway above. Perhaps most touching of all, standing on a plinth by the designer’s desk is a darling white figurine of the sculptor Don Brown’s wife, Yoko. Her slender, childlike form is dressed in little more than a pair of chunky wedges. They’re not unlike the substantial, clog-like footwear that was Phoebe’s trademark during her tenure at Chloé, come to think of it, or the wooden-soled platforms that marched down the runway for Céline.

The specific pictures Phoebe is referring to, however, are those pinned to the giant mood boards that line her office wall, and which formed the basis of the catalogue given out at the show. From an extraordinary mid-’70s image of Cher attired in a constellation of Bob Mackie feathers and bugle beads and energetic reportage shots of naked ’60s festival revellers, to punchy David Sims/Melanie Ward editorial dating from the early ’90s, these pictures were culled from a personal collection of tear sheets she has been amassing since the age of 13. With which, incidentally, she has plastered the walls of her bathroom at home in the leafy Brondesbury district of North West London. “What you’re seeing in the book is my universe. By putting it on a seat at the show, I didn’t want it to be at all promotional,” she explains in the soft, slightly cautious tones of someone who wants to be open and understood while also being mindful of her new position. “The only reference to Céline is a photo I took of the new logotype.”

“I hope the clothes are worth it. They’re well made and the fabrics are beautiful. So I believe they will last, as an investment. They’re not something just to be thrown away.”

Phoebe’s voice is characterised by long vowels and the occasional glottal stop in place of a “t” that endearingly gives away her North London upbringing. The metropolitan accent is in slight contrast to the classicism of her looks: the swooping hollow under her cheekbones, the pointed arch of her eyebrows and the ravishing widow’s peak that gives her heart-shaped face a dashing “principal boy” air. Huddling under a very precise, knee-length camel coat from her first pre-spring collection for Céline, the 36-year-old designer is wearing a sage cashmere sweater, slim jeans and a pair of black “tabi” Margiela ankle-boots. Her sole adornments are a tasteful pair of gold stud earrings and fine gold double wedding bands. But for the fact that Phoebe goes without socks on a chilly day, the cloven toes and spindly stiletto heels of the boots are the only clues to her fashion provenance. From the ankles up, she could just as well be a very chic curator or a glamorous academic.

“Some of the images are iconic,” she continues, thumbing a spread of an incandescently sexy, young Charlotte Rampling. “Others are random: pictures of animals, pages from Sunday supplements. Someone said the book looked very autobiographical, and I guess it is nostalgic – my being born in ’73. Or familiar: it reminds me of my mum.”

In an economic climate calling for pragmatic clothes for working women, it is perhaps unsurprising that the new crop of – principally British, 30-something – designers exerting the most impact upon fashion are currently reinvestigating the period of their childhood. For it was of course the 1970s when the notion of women “having it all” – the family and the job – was a hotly contested topic at middle-class dinner tables in Northern Europe. Hence the focus on believable daywear, the sturdy fabrics and sympathetic cutting and, above all, the charmingly frumpy palette of camel, khaki and beige. Each of these elements of early ’70s dressing were notable in the Spring/Summer 2010 presentations by Stuart Vevers for Loewe, Hannah MacGibbon at Chloé and Phoebe Philo for Céline.

On one hand, Phoebe refers to her luxuriously utilitarian collection as “a wardrobe, a practical ABC of clothes” – an understatement that is made explicit in Juergen Teller’s inspired advertising campaign, which rejects the celebrity model in favour of prosaic close-ups of the garments. Yet Phoebe has deeper associations with the 1970s lifestyle from which the Céline aesthetic emanates. “The image I have of my mother at that time; she seemed to have a freedom that I think we long for now, a lack of the pressure that there is today. Life was much simpler.” Phoebe seems to become aware that her observations might be painting an over-simplified idyll of stay-at-home, Stepford Momdom because she quickly reminds me that her mother, Celia, had a career in the decidedly blokey field of designing music packaging. She famously created the LP cover of David Bowie’s Aladdin Sane. “My mum did work as a graphic designer, but it was in a more freelance way that fitted around having a family. From my point of view now, nothing felt like a rush. She didn’t learn to drive until I was five, so there was lots of walking, with my little brother in the buggy.”

Crucially for Phoebe, her mother’s family-centred itinerary was allied to an identifiable uniform, one with a silhouette that should be recognisable to the legions of young women nicknamed “the Philophiles” who so adored the nipped-in shoulders of Phoebe’s tailored jackets and the ease of her boyish pants at Chloé. “She wore very practical clothes and had the same pieces for ten years. Things that lasted: a plimsoll with a lovely, washed-out old wide-leg jean and a little tight T-shirt,” recalls Phoebe. “They didn’t have much money at that stage so didn’t consume much.”

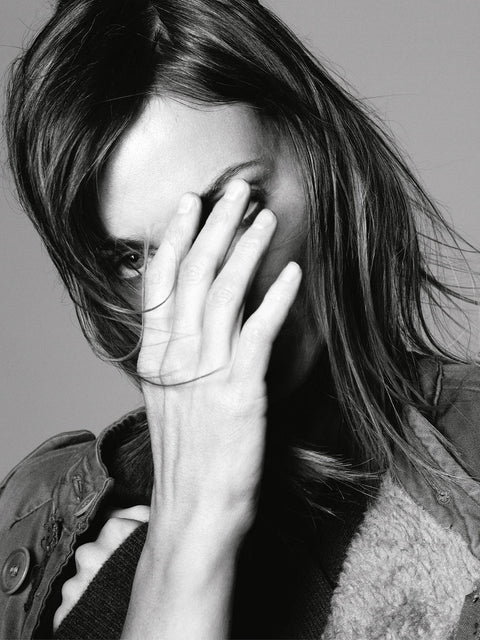

A series of personal portraits of Phoebe by David Sims, taken at Spring Studios and at her home. She is wearing her favourite pieces from her Céline collections and her own wardrobe. In this series, Phoebe wears, respectively, a vintage parka with a knit cardigan from the CÉLINE pre-spring 2010 collection, a CÉLINE tuxedo suit, also from pre-spring 2010, vintage LEVI’S and a vintage sheepskin coat.

How, I wonder, does that memory of stylish frugality square with the current prices of Céline? The jacket draped over Phoebe’s shoulders is currently retailing at €2000 in the Selfridges department store situated four blocks along the road from the Céline building.

It’s expensive.

“It’s expensive,” she echoes in agreement, wincing at the paradox.

Is it worth it?

“I hope so,” she says sincerely, pulling the thick cashmere closer to her body by its lapels. The workmanship of the redoubtable Caruso factory in Florence now manufacturing Céline’s tailoring is evident in the precision of the beautifully finished seams inside. “They’re well made and the fabrics are beautiful. So I believe they will last, as an investment. They’re not something just to be thrown away.” If this is sounding less like a prescription for modern dressing and more a formula for modern living, it should be remembered that these are the words of a woman who in the past ten years has gone from being Stella McCartney’s Girl Friday to a spokesperson for her generation.

I remind Phoebe of the first time that I met her. In November 2005, I was despatched to interview her on behalf of a Japanese magazine. My brief was partly to celebrate the skyrocketing sales figures at Chloé, where she had been creative director since 2001. Revenue from her girlish, pin-tucked baby-doll dresses and heavy leather accessories had increased 60% in the previous year alone. But I was instructed mainly to focus on her lovely home life with her husband, the terribly handsome and debonair art dealer Max Wigram, and their new baby Maya Celia Sally (who is named after African-American poet Maya Angelou and Phoebe and Max’s respective mothers). “Up, up, up!” were the words of my commissioning editor.

What I got on tape instead that day were the remote responses of a shell-shocked young mother who was clearly finding balancing the demands of work with her family almost unbearable. Though she had successfully negotiated with Chloé to work from a studio in London to minimise the punishing commute to Paris that was eventually cited as her reason for leaving, our discussion was dominated by her frustrations over being regarded as inseparable from the brand and her feelings of being a commodity. “There is Chloé and there is me,” she emphasised. “I am not just Chloé.” Phoebe herself looked as winsome and dainty as she did in the pictures I had seen. But she was somehow less ebullient than the rambunctious party girl with the fake nails and the great dance moves that I had read about.

“I wasn’t living a true life,” she says now of that period. “My life with Max consisted of fitting a week’s worth of conversations and everything that goes on between a couple into two days: Saturday and Sunday. It felt manufactured and fake.” It was to be the last interview Phoebe gave as creative director of the company before stepping down at the start of 2006. “Leaving Chloé felt like the most honest thing for me to do; for my integrity, my husband and my daughter.”

In a confab between two married women in their 30s – one with children, the other without – one topic is unavoidable: what’s it actually like, giving up work? Phoebe grins and leans forward, conspiratorially. “The first year felt just fabulous.” Without deadlines, agendas or having to be anywhere at a given time, she did lots of the things she hadn’t had time to do: catching up with friends, spending time with her husband and going to the country to ride. But didn’t she experience a sense of loss, a fear that she’d never be able to return? Phoebe shakes her head, quizzically. “It might sound a bit unrealistic, but I honestly left with no plans to do anything. Maybe that would be it with me and fashion. My mum had adapted her career to suit so I think I was confident that I could, too, if need be.”

Becoming pregnant for a second time, with her son Marlow, allowed Phoebe to experience pregnancy and birth without eventually having to return to work. For a time, she carried out consultancies at her home, most notably for GAP, but working from home lacked the dynamic and rigour of studio life. “That weird energy of kids in the background felt quite wrong,” she remembers. “Within a couple of years, I started to want it back. I wanted that place to go.” In addition to recapturing her creative autonomy, the other motivating factor was the issue of retaining her financial independence. “The one thing I have always had is my own income. I had a paper-round when I was 13,” she smiles, enjoying the knowledge that slogging a sack-load of tabloids around a housing estate in the middle of the night isn’t perhaps the kind of work experience one might expect from the head of a luxury fashion label. “That feeling of being paid on a Saturday is important, empowering; the money was mine to do what I wanted with. It wasn’t that Max couldn’t afford to keep me but that I really don’t like the idea of being a kept woman.”

With Phoebe being the major breadwinner and her husband working as his own boss in the art world – arguably one of the most progressive fields when it comes to gender dynamics – was there no question that he might have been the one to stay at home to mind the children? “No. What Max is very good at, though, is taking time off. He’s not as answerable to so many people as I am. If he returns from a big trip and is tired, he takes two or three days off to recover. That’s unheard of in this industry.” It is a life lesson Phoebe has taken on board for herself. She recognises that she occupies a privileged position.

“I have so many friends that are single – really intelligent women that are attractive in every single way – who are unable to commit to men. I worry that women are becoming so independent and dominant that they are losing any sense of softness or acceptance. I sometimes have to ask myself: “What do I want to be, right or happy?” Our expectations of men are becoming supersonic. These women expect someone that looks like Brad Pitt, with the brains and creativity of Lucian Freud, and they think these qualities will merge together into someone who will love them and be totally accepting of all of their weaknesses. It’s just not going to fucking happen! The one thing I learnt from my mother, who is lucky to still be with the love of her life, is just not to ask for too much.”

That said, Phoebe has asked for and attained a great deal for a 36-year-old. Think of her critical acclaim, her business acumen, her status as a role model for young women and the fact that after 14 years in fashion, the press still love her. In comparison with her friends’ unrealistic expectations of the perfect catch, the dogged, unconditional support of a real, ordinary man isn’t something she has merely settled for.

“He’s a really strong man, Max,” says Phoebe. “And I really love him and I think he really loves me and I really trust him. I know he wants the best for me and he’s very gentle with me when I am feeling insecure and scared. He’s very reassuring…” Embarrassed that she’s divulged more than she meant to, Phoebe adjusts her tone. “I mean, he can be a complete wanker as well!”

“Céline doesn’t have a history of an iconic designer or much of an archive. It can be difficult for designers to step into someone else’s shoes. But for me, Céline was a clean slate.”

It is unusual to hear a successful designer discussing the anxiety and fearfulness that inevitably accompany the relentless schedule and media intrusion that is their daily life. But not unheard of. When Tom Ford admitted to suffering depression after leaving Gucci in 2004, it must have been a huge relief to his peers that the designer’s candour did nothing to diminish his myth. For Phoebe, it only makes her – and her exclusive brand – easier to identify with. “I have massive fear around work,” she says. “I definitely experience anxiety and I can be fearful.” Phoebe states that she has tried everything from prescription drugs to therapy to help her combat work-related stress but ultimately she finds meditation the most helpful. She leads me over to the large sash window behind her desk. “All I have to do is take five minutes, look at the sky, and think about the bigger picture, not the very little picture that I’m involved in at that moment. I imagine the world and not me in a room with a bunch of clothes.” Phoebe pauses. “It sounds very annoying.” She switches the conversation to her love of junk food and the fact that a bucket of KFC would be her death-row meal. “Not very Céline,” we both agree.

But what exactly is Céline?

When Bernard Arnault announced in September 2008 that Phoebe would be returning to fashion to redefine the moribund brand, it was universally acknowledged that she had her work cut out for her. Founded by Céline Vipiana in 1945 as a children’s footwear supplier, and perceived as a wannabe competitor to Chanel, the brand has enjoyed pockets of success – most recently Michael Kors’ seven years of designing for the brand, from 1997–2004 – but it subsequently foundered under a succession of unsuccessful replacements. Phoebe must have had qualms when the job came up. “I think it’s probably best we don’t put my first thoughts down in print,” she hoots, covering her face with her hands. But in the event, the brand’s lack of design integrity proved to be its most attractive quality. “After I’d had time to absorb it, I realised it was an interesting project. Céline doesn’t have a history of an iconic designer or much of an archive. It can be difficult for designers to step into someone else’s shoes. But for me, Céline was a clean slate.”

Phoebe means this quite literally. Rather than stealthily integrating the new designs into the existing Céline stock, she reputedly ditched every last gold-chain handbag in a dramatic overnight cleanout last November.

Now the company’s 100 shops worldwide are filled with chic, graphic clothing that fuse the luxury materials and high-quality manufacturing available at Céline with the urban touches Phoebe was loved for in her previous jobs. In a standout look from the spring show, a sharp black leather T-shirt was teamed with a short, A-line skirt in linen canvas, the edges of its hem and central pleat outlined with a slick of black calfskin. The sumptuous leathers for which Céline is known were also present in a glorious array of accessories – the low-key bags are a canny nod to shifting tastes – but the initial priority was getting the apparel just right, as Phoebe herself would wear it. “I feel like I design things for right now,” she says. “The anchor of my kind of classicism and then the more fanciful things around it are what make my collections personal, different from those of other designers.”

Today, a purposeful, more grounded Phoebe is also using this fresh start at Céline as an opportunity to build the ideal company structure, one that will allow her to protect her quality of life whilst the brand continues to flourish around her. She tells me that in the various discussions preceding her eventual decision to commit to the company, her being based in London was always “non-negotiable”. And this time, not everything will rest on her being in the studio until all hours. Though the clothes and the corporate communications bear Phoebe’s unmistakable personal touch, she is insistent that they are the work of a senior and experienced team of international designers that will help her carry the can. “The days of me staying until eleven o’clock are no longer. I’ve come back to work with the strong belief that it is possible to be a mother and to do this job.” And as ever, Phoebe is the best model for her own designs. From the woman who famously said that she refused to design a three-legged trouser, her pragmatism is always at the fore. “There are lots of things I’ve done for Céline that I would personally buy, and I can put myself into looks from the collection. But I’m not everything to the brand and I quite like that.” She may hold the secret to modern dressing and have modern living down to a fine art, but what Phoebe has learnt is that having it all doesn’t necessarily mean doing it all yourself.

Text by Penny Martin

Portaits by David Sims

Styling by Camilla Nickerson

Hair: Paul Hanlon at Julian Watson Agency. Make-up: Hannah Murray at Julian Watson Agency. Photographic assistance: Bjarne Jonasson, Baud Postma. Digital operation: Sam Garas. Thanks to: Spring Studios.

This profile was originally published in The Gentlewoman n° 1, Spring & Summer 2010.